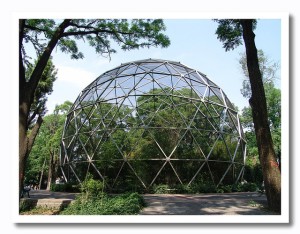

(Photo:Statue-Blue Water Park, Guadalajara. Some rights reserved by ego2005 .)

“Grandpa,” I said walking in to Grandpa Next Door’s house; without knocking, of course. “I’m here to bug you some more.”

“Hey, Jose!” He says. He gives all of us grandkids nick-names. Mine is Jose. Sometimes Jose Jimenez which is a reference to some character that a Mexican comedian invented. Now that I think about it, it doesn’t really make sense, but I got used to it after about two decades of him calling me that.

I sit down and start catching up on my novelas. It’s a particularly strange one with the Mexican version of Tyler Perry prancing around in drag. My Tío Corney is also there and we make fun of the novela together and catch up on how his adult daughters are doing. It’s weird trying to figure out when/how to launch into questions about my Grandpa’s past. It’s not like I ever strolled up to Grandpa Next Door during Christmas when I was 7 and asked, “So Grandpa, what is your earliest memory?”

“So when we last left young Nabor and Emilia. Los jóvenes.” I say in my best 1960’s narrator voice. “They were returning to Mixtlan.”

“Los jóvenes.” Grandpa repeats. “A long time ago.”

* * * * *

Nabor and Emilia needed money and they needed it fast for soon they would have a baby to take care of. In his scramble to find work, Nabor ran into a man who offered him a field that he could plant on for the price of half his harvest. The land-owner had already plowed the field and was going to plant it himself when he was unexpectedly called away to Sonora. Nabor agreed to the man’s terms, rented everything he needed, and went to work planting corn and beans. The soil of Mixtlan was not as giving as the soil of Miraplanes and Nabor had a very poor harvest that year. The land-lord took his half; then Nabor paid for what he rented. A very small amount of the crop was left over and Grandpa Next Door ended up losing his shirt on the deal. By now, Cornelio (Tío Corney from earlier!), their first child was born. Nabor and Emilia needed money and they needed it fast.

Fortunately, Great Grandpa Toribio had work for Nabor to do on some land that he owned. He agreed to pay Nabor twenty much needed pesos a week for his time. The job consisted of repairing old tannery shacks that had suffered terrible flood damage and then figuring out how to prevent the river from destroying them again. Nabor began the backbreaking labor of unearthing the huge stones that were used as the foundation of buildings back in the time that the old shacks were built. He used these stones to reinforce the perimeter of the shacks so they would be able to withstand the river when it flooded. After that he rebuilt the shacks themselves. He did such a great job that his dad laid him off because there were no other shacks for him to repair. That’s the thing with construction; you’re always working your way out of a job.

Side-note: Grandpa Next Door told me with pride that these tannery shacks, which are now over 100 years old, are still standing to this very day.

Nabor and Emilia were, once again, fed up with Mixtlan. They decided to look for a better future in the northern province of Sonora so they booked a first class flight and Fed-Exed their belongings to their summer condo.

They began the move north by catching a ride on a truck bound for Ameca which was the nearest train station. Emilia and Cornelio, who was only 6 months old at the time, rode in the cab with the kind driver while Nabor rode in the bed. The truck driver had just delivered a bunch of charcoal which at the time was used for cooking and heating. Because of this the truck bed was full of sacks that were saturated with black dust. The journey to Ameca was 8-9 hours through sharp-turning, mountain switchbacks. When the young family got there, Nabor looked like one of those racist actors who used to perform in black-face.

In Ameca, they stayed with Emilia’s tía who graciously allowed Nabor to take a bath. For a week they were cared for by this kind relative until the train to Guadalajara finally arrived. It was an engine touting only one box-car. Another 6-7 hours later and they were in Guadalajara waiting for yet another train that would take them to Magdalena, Sonora where they hoped to prosper.

There was to be no leaving the train station in Guadalajara once they arrived; no staying with a kind auntie. This station was packed with thousands of people just as desperate as the young family and so they had to stay to save their spot in line. For two weeks they lived in the now world famous Blue Water Park in Guadalajara. While they were there Nabor befriended a middle aged train porter. The porter seemed to have compassion for Nabor who was obviously in way over his head.

Some rights reserved by ego2005

“Where are you trying to get to?” the porter said.

“Magdalena,” Nabor said.

“Ok, I’ll go find out how much it costs.”

The porter was in uniform, but for all Nabor knew he didn’t even work for the train company. The porter returned with the supposed ticket price.

“It’s 32 pesos. Do you have money?” the porter said.

“We have very limited funds,” Nabor said.

“Ok. Give me the money and I’ll go buy you the tickets.”

The porter must have noticed a suspicious look in Nabor’s face.

“Look,” the porter said pointing to a badge on his uniform. “My badge number is 32 so you don’t think that I’m going to rip you off or anything.”

The man’s badge number being the same as the price of the ticket did little to put Nabor at ease, but he didn’t have many alternatives. Even if he went to the ticket booth himself, the people there could lie to him just as easily. Eventually, he was going to have to trust one of these strangers. Nabor gave the money to the porter and prayed that he was a good judge of character. “Porter 32” took the money and disappeared into the sea of people waiting for the train of new beginnings.

Nabor and Emilia tried to keep their minds occupied while a large chunk of their sparse resources floated in limbo. As they conversed with other people at the train station they learned of a potential problem with actually getting onto the train. They learned that when the train arrived in Guadalajara it was basically a free for all. On top of that, the train didn’t stop for a very long time for fear of over-crowding. After considering the thousands of people that they had to contend with, the luggage, and the six-month old, Nabor and Emilia realized that it was going to be impossible to get on the train without help. But who could they trust? They couldn’t afford to pay very much for help and they may have just been shorted 32 pesos.

Just then, Porter 32 arrived with the tickets. Nabor decided to ask him to help them when the train finally came.

Somehow, the arrival of the train that everyone had been waiting for, for two weeks, still managed to be a surprise.

“Come quickly,” Porter 32 said. “The train is on its way.”

By the time Nabor collected their few possessions, the train was already being mobbed. Porter 32 jumped into it and reached out his hand for Emilia and the baby. Nabor hurried and managed to get them to Porter 32 successfully. Then Nabor threw the luggage to him, but there was a problem. The train not only didn’t stop for very long in Guadalajara, but, because of the throng of humanity trying to get north, it didn’t stop at all. Nabor had to run to catch up after throwing the luggage in. Just as he was about to get in, the doors of the train closed on him. He practically had to sprint now to keep up. Nabor’s family was being carried away to Sonora without him.

I really like this. Tell me more. cz

LikeLike

Josiah…..I’m thoroughly entertained by your stories. I must warn you, though, Do Not Say Mean Things About Yaqui’s. We are really nice and sometimes intelligent people. My dad was born in Sonora, Mexico. I’m so sad that he died before we could ever have any meaningful conversations about his life. Keep up the good work…love you. Carrie

LikeLike

I’ve got nothing, but love for both you and the Yaqui’s, Carrie. Thanks for reading and I will definitely keep the stories coming.

LikeLike

lOVE YOU

LikeLike